Posted 1 month ago

Thu 25 Sep, 2025 09:09 AM

October is a celebration of the people and history of the African diaspora. In this article we will be delving into the lives and work of three Black sustainability pioneers as well as the impact students can make in advancing decolonisation across their university.

While the month of October may be dedicated to the remembrance and celebration of Black History, it is by no means the only time you can do so. The Guild’s More than a Month campaign seeks to draw attention to marginalised groups and reinforce the need to work towards an equitable society at all times. More information about getting involved can be found at the end of this article.

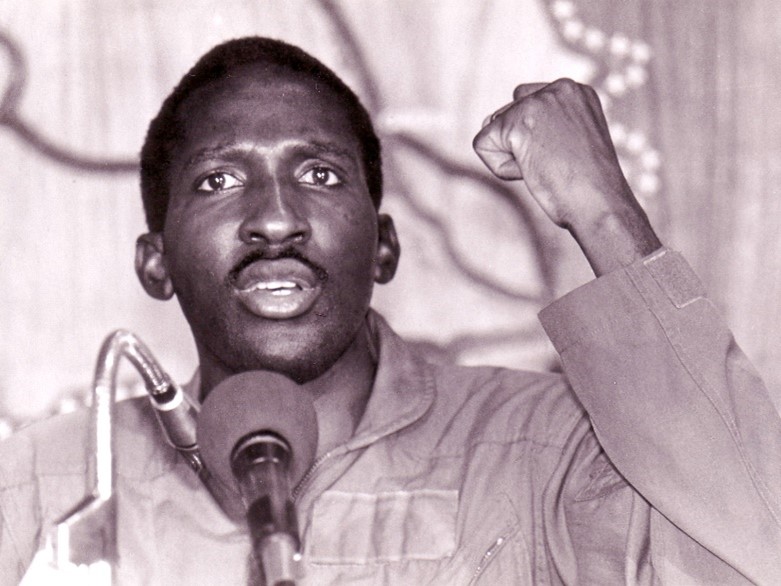

Thomas Sankara

A towering figure in 20th Century anti-colonialism and anti-imperialism, the revolutionary Thomas Sankara was born in 1949 in Upper Volta, now Burkina Faso. Following a rigorous education and illustrious military career, Sankara led a faction which, in 1983, deposed Upper Volta’s ruling elite and severed ties with France, the country’s colonial oppressor. He renamed Upper Volta to Burkina Faso, meaning ‘Land of Incorruptible People’. His government rallied against social, economic, and societal ills.

Sankara did not limit his ambitions for the country to improving socioeconomic conditions. He recognised that over-farming and over-grazing had been causing desertification in the Sahel region, which, left unchecked, would eventually lead to the region being swallowed by the Sahara Desert. In response to this threat, the Sankara administration’s programme of tree-planting began in April 1984 and within fifteen months over ten million trees had been planted. These trees served not only as a means of preventing soil erosion, but also as a sustainable fuel source for inhabitants of the region.

-----

Thomas Sankara at International Conference on Trees and Forests, Paris, February 5, 1986.

“Yes, the problem posed by the trees and Forests is exclusively the problem of balance and harmony between the individual, society, and nature. This fight can be waged. We must not retreat in face of the immensity of the task. We must not turn away from the suffering of others, for the spread of the desert no longer knows any borders.”

------

Tragically, Thomas Sankara was assassinated in 1987. Nevertheless, his legacy lives on in those who continue to fight the expanding Sahara. The Great Green Wall project, headed by the African Union, is a continent-wide expansion of Sankara’s initiative, and is around a fifth of the way to achieving its goal of restoring 100 million hectares of land in a belt which spans the continent.

War and lack of funding is threatening the delivery of the project on its intended timeline. This only reinforces the need for transnational cooperation for the benefit of African people, as Thomas Sankara initially sought to do in the blossoming state of Burkina Faso in the 1980s.

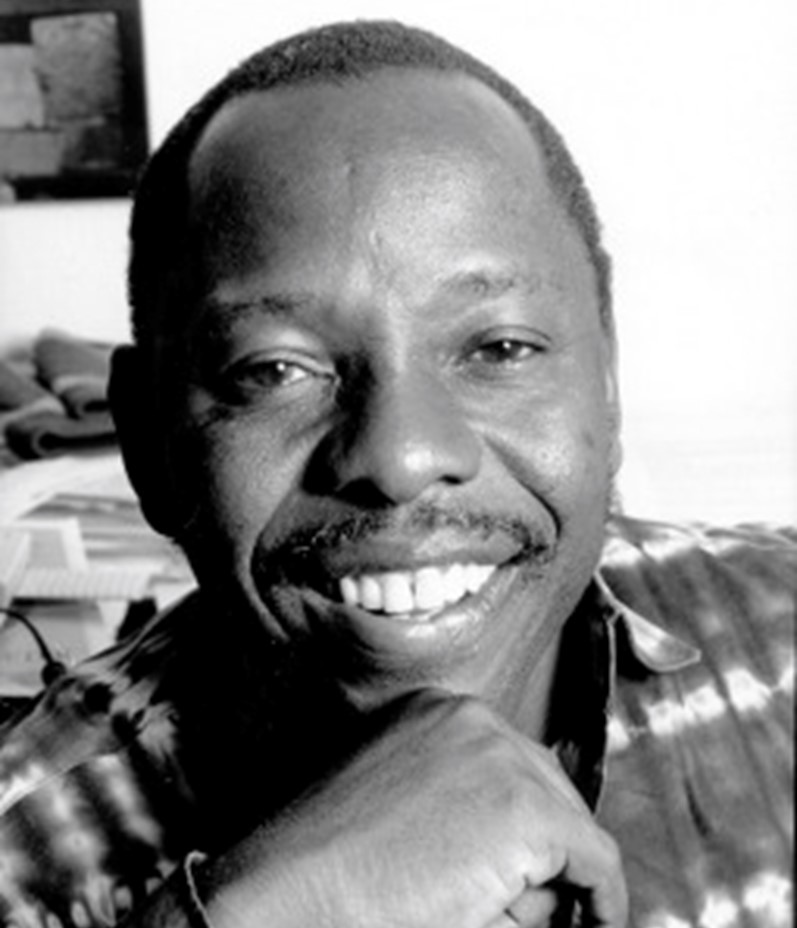

Ken Saro-Wiwa

Kenule “Ken” Saro-Wiwa was born in 1941 near Port Harcourt, Nigeria. The son of an Ogoni chief and forest ranger, he grew up in a family with a profound appreciation for the natural world, as well as the means to study it. Passionate in English, history, and drama, he began his adult life in journalism and television production, before being recruited as a government advisor by military dictator Ibrahim Babangida, who sought Saro-Wiwa’s help in the transition to democracy. Doubting the sincerity of Babangida’s purported intentions, Saro-Wiwa resigned from his post and put his mind to grassroots political activism.

In 1990, he joined the Movement for the Survival of the Ogoni People (MOSOP), an environmental justice movement based in the Niger River Delta. The region had been exploited by oil companies, including Royal Dutch Shell, since the 1950s. The Ogoni people who inhabited the region lacked the political influence to even claim a share of the wealth extracted from the land, let alone hold to account the companies responsible for environmental crimes. Through his literary and campaigning work he gave a voice to a minority, giving national, and even international, prominence to their cause. His activism, and that of MOSOP, led to Shell’s withdrawal from Ogoni lands in 1993.

-----

“In this country [England], writers write to entertain, they raise questions of individual existence...but for a Nigerian writer in my position you can't go into that. Literature has to be combative. You cannot have art for art's sake. This art must do something to transform the lives of a community, of a nation.

Ken Saro-Wiwa

-----

However, Saro-Wiwa was arrested by Nigerian authorities in 1994 on accusations of complicity in the deaths of four Ogoni chiefs at a political rally. He was subsequently executed, leading to international condemnation and the suspension of Nigeria from the Commonwealth of Nations. The resumption of Shell’s Ogoni operations following his execution led many to see Saro-Wiwa as a direct victim of imperialist aggression, and his death highlighted the extents to which extractive industries would go to to maintain their profitable operations. Today, Saro-Wiwa is considered a martyr by environmental activists worldwide and is memorialised across the globe, including in the Guild where we have a room named after him.

Dorothy Kuya

Sustainability is not just about the environment. The United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) include a whole range of issues which should be addressed to achieve sustainable growth – sustainable cities and communities (goal 11), decent work and economic growth (goal 8), and reduced inequalities (goal 10) were all things Dorothy Kuya fought for her entire life.

Born in 1933, Kuya was a formidable campaigner. She was active in Communist circles from age 13 and her work included becoming the first Community Relations Officer for Liverpool Community Relations Council, fighting against South African apartheid, as well as becoming a Member of the Granby Residents Association, fighting against the demolition of the Granby area by the Council.

Granby and the wider Toxteth area are some of the most racially and ethnically diverse areas of Liverpool. The 1981 Toxteth riots, sparked by heavily racialised stop and search by Merseyside police, led to a government crackdown of the area, with an attempt to disperse the community, by moving, selling up or transferring their social housing - something Margaret Thatcher termed the "managed decline" of the city.

Thanks to the work of Kuya and others, the community was able to fight back against the planned demolition of the remaining Victorian housing. One street was turned into an open art gallery, (winning the Turner Prize in 2015) and the Granby Winter Gardens, a sustainable community centre initiative was created.

In her later life, she worked with the National Museums Liverpool and helped to open the Transatlantic Slavery Gallery in 1994, inviting Dr Maya Angelou to speak at the opening night.

-----

“This was once the heart of Liverpool 8. It is not only decent homes that have been destroyed, it is a whole community.”

Dorothy Kuya

-----

Dorothy Kuya also has a presence here at The University of Liverpool. Students expressed concern and discomfort at Greenbank Halls of Residence being named after William Gladstone – a former prime minister and statesman who lobbied for home rule for Ireland and had historic familial involvement in the slave trade. The campaign to have this name changed spanned three academic years, consisting of multiple actions ranging from Change It petitions as well as writing open letters and meeting with senior University leaders. Adnan, the Guild’s previous president, utilised student voice as well as the wider social pressure resulting from the BLM movement and other decolonisation efforts from other universities and cities – such as the removal of statues of slave trader Edward Colston in Bristol to All Soul’s Oxford College removing “Christopher Codrington” – a Barbadian slave owner – from their building names.

In the end, following a cross-campus ballot for new names, the halls were renamed in celebration of Dorothy Kuya.

To find out more about Kuya, Writing on the Wall and National Museums Liverpool have worked on her archive since her death in 2013, and regularly put on events in the city as well as showcasing some of her important work and archival materials.

More than a month

This article has described the lives and actions of three iconic figures in Black history, but history is made not only by individuals, but also by communities. Regardless of the community you consider yourself a part of, there’s always work to be done to resist inequality, continue the fight against colonialism, and improve the quality of life of the world’s marginalised communities.

You can get involved in the Guild’s liberation groups, which help to give a voice to marginalised communities and coordinate action where you see fit. Take a look at the liberation hub page to learn more.

Finally, if you want to run events to commemorate Black History Month, there’s no better place to start than your hall’s HSC! You’ll work in your committee to plan and run events – the sky is the limit! Take a look at the HSC page to learn more.